HQ Review: Space Station’s Winter Weekend with Chew + Spit

Dyke Devotions, the second iteration of Chew & Spit, took the stage at Hope United Church of Christ on January 17th. The performance featured fourteen dancers, including Marlee Doniff, the project’s architect, who appeared briefly in a cameo at the top of the piece.

The dancers meandered across the stage, speaking casually to each other and to those still finding their seats before the show began. Eventually, they settled unceremoniously along the stage’s perimeter at the audience’s feet. In this intimate venue, the audience sits in the round, pressed against the “stage,” marked only by the carpet’s edge and the start of the black dance floor. The closeness of the dancers to the audience would become an integral part of the experience of this work.

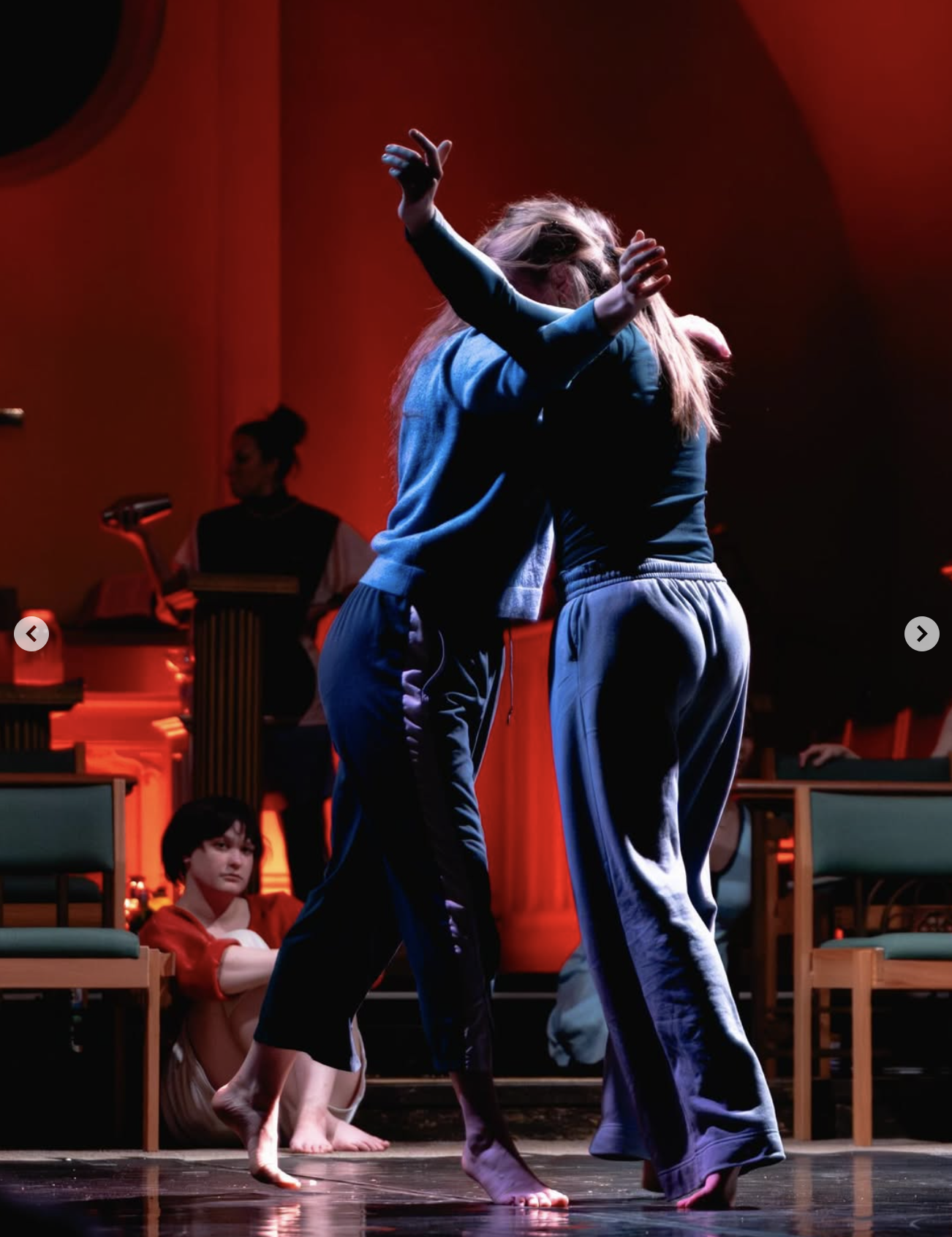

Once the dancers were settled, Marlee came out and knelt. They prayed haltingly to Mary, Mother of Jesus, departing from a script many of us know so well. Then they left the stage to sit with the audience as the dancers moved from the periphery to lie face down at odd, jutting angles all over the stage. Two dancers, now on their feet, began a methodical walking pattern in unison. They stepped over the prostrate dancers’ arms, legs, and heads, mumbling numbers to each other as they went. The duo came so near the audience that they caused many to shift in their seats and nearly collided several times. Another duet emerged, and—arms wrapped around one another’s waists—the two dancers spun violently, releasing one another only to stumble away blindly and then back again. The container of the piece began to strain, even from these first moments, to hold the bodies and movements. These bodies teetered near a true loss of control, and the effect on the audience was visible: those closest would readjust themselves in their chairs or protect their drinks. As a viewer, this was not the first time I, too, felt unease—though also a thrill of excitement—at the near miss of a body being propelled through such a crowded space.

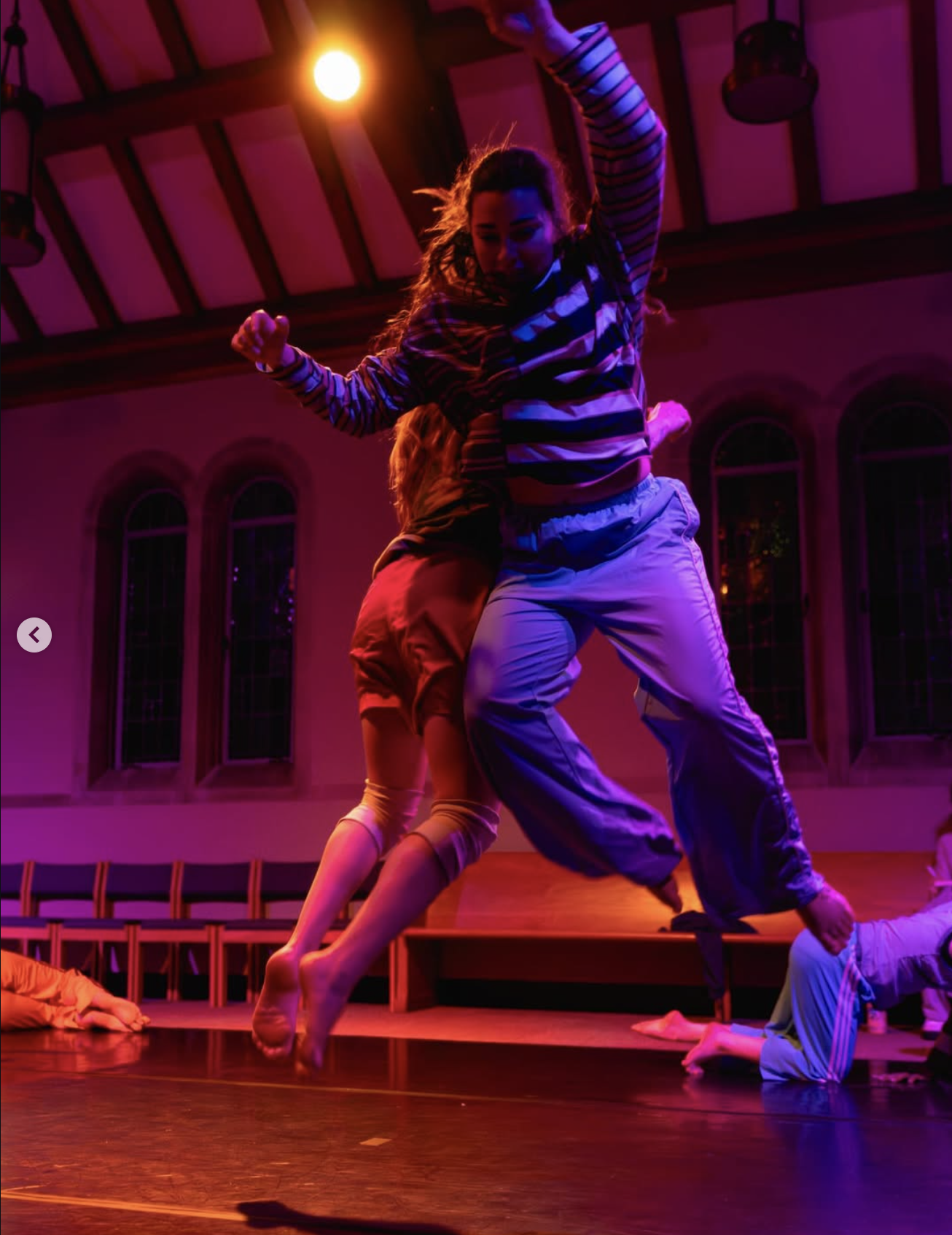

The dancers’ movements were often belabored and cumbersome, with only sporadic eruptions of virtuosic, almost balletic lines, jumps, and turns. These moments appeared nearly out of place against the otherwise exhilarating tumbling and crashing momentum of the work. Several times, the dancers clambered over one another in a pile, the contortion of limbs and heads suddenly emerging as a sculptural mass of unruly bodies. The general wildness crescendoed in a particularly exhilarating and alarming moment of two dancers running, jumping, and slamming into each other repeatedly, each taking turns sending the other flying through the air and crashing back to the ground, breathless. This moment, repeated to audible gasps by the audience, had an astonishing effect and remained a lingering image from the night. Somehow, despite this near-violent approach to partnering, the impression was not of aggressions born of rage, but of fully embodied, fully committed PLAY. The moment was alive with risk and effort.

The piece seemed to play on ideas of uncontainable bodies in varying states of unruliness, exhaustion, and excess. There was no reticence among any of the dancers, no suggestion of boundary between bodies or of resistance to whatever moment they found themselves in. All seemed to be of one mind, moving together—towards what end? Enlightenment? Euphoria? The religious undertones suggested at the top of the show with the prayer to Mary emerged again in the form of song choice (Ave Maria) and in a peculiar task. Gathered together in a large, trembling clump in the center of the stage, the dancers passed around a large jar. The small bits of paper they pulled from the jar were secrets deposited anonymously by the audience upon entering. One by one, they were removed and read aloud; some funny, some pained, all very relatable. The moment played as a sort of makeshift confessional, and the levity and laughter the secrets produced took the form of absolution.

Dyke Devotions was full of contradiction: offering something approximating belonging, coming close to joy, but also volatile and precarious. Demonstrating risk-taking, there was nonetheless a receptivity to each body and a softness to each moment of collision. Throughout, the audience seemed both alarmed and delighted.

In the program notes, Marlee discusses the use of the word “dyke” in the title and mentions its association with volcanic structures: “I don’t know much about volcanoes, but I have come to understand the dyke of the volcano to be the channels that magma travels through before it bursts through the surface to become lava.” This factoid provides an evocative and apt description of the piece. Perhaps the work reflects a state of built-up tension, which explodes in dazzling spurts. Or maybe it is movement, born from a tremendous amount of pressure, emerging from the earth dramatically, violently, and spectacularly.